The concept of a balanced scorecard was developed by Dr. Robert S. Kaplan of the Harvard Business School, and Dr. David P. Norton, and is explain in their book Translating Strategy into Action. The Balanced Scorecard. The basic idea is that the, vision and strategy of an organization can be expressed as a set of goals and their associated objectives, measures, target values and initiatives. I covered defining goals and objectives for system design in a previous article. The Balanced Scorecard approach extends the scope of goals and objectives to the entire enterprise. Originally this approach was suggested as a business-measurement system but it has evolved into a business-management system. By continually measuring progress toward the objectives, the execution of a strategy can be monitored, corrections can be made, risks can be reduced, and the chances of success increased.

The key innovation of the balanced scorecard approach grew out of a simple realization. Most businesses only track progress in a measurable way from a financial perspective. Kaplan and Norton claimed this, single perspective view was “unbalanced” and that this lack of balance is inappropriate for “information age” corporations. They identified three additional perspectives, or areas of concern, that most businesses should also monitor. Listed below are the four perspectives they identified.

- Financial

- Customer

- Internal Processes

- Learning and Growth

In subsequent analyses it has been found that companies which use a balanced scorecard and place greater emphasis on the Internal process perspective are more successful. These companies typically assign approximately 1/3 rd of all objectives to internal processes and then equally divide the remaining objectives among the other three perspectives. This is the essence of the balanced scorecard. Kaplan and Norton claim that just 20 to 25 objectives, with measures, across the four perspectives can be sufficient to communicate and implement a strategy. There are entire books, software systems, and companies dedicated to the explanation, implementation, and monitoring of balanced scorecards but, in principle at least, the approach remains simple.

Defining Objectives with both Leading and Trailing Indicators

As the Balanced Scorecard developed from a business-measurement tool into a business-management tool it became more important to track leading indicators of progress toward goals as well as trailing indicators that measure achievement of goals. In some cases a single objective can have both leading and trailing measures that can be used to ensure progress is being made and indicate when the objective has finally been achieved.

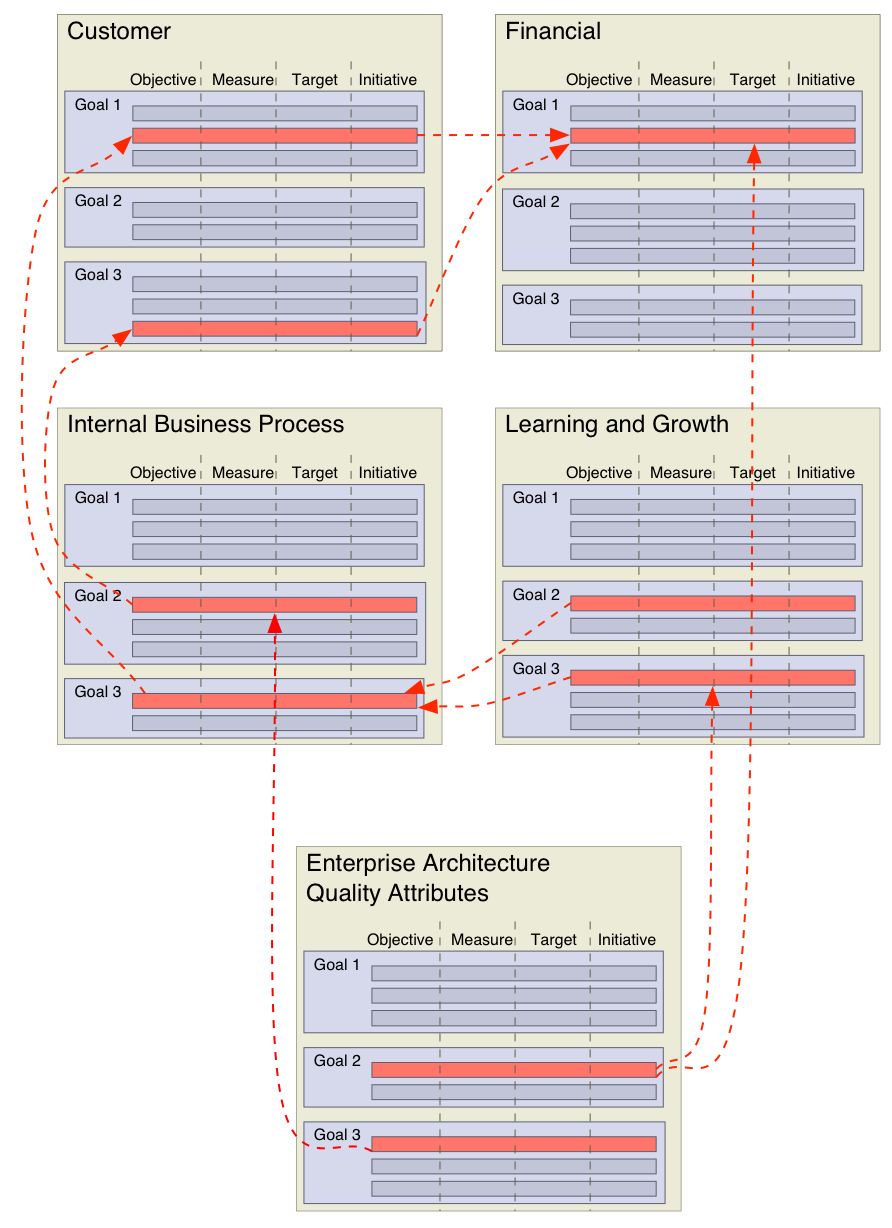

Linking Objectives to Create Cause and Effect Relationships

Kaplan and Norton state that

A strategy is a set of hypotheses about cause and effect.

They also point out that while many balanced scorecards are just collections of objectives grouped into four perspectives the best scorecards link these objectives into chains of cause and effect. These chains typically link objectives across all the perspectives. They often start with objectives for learning and growth and show how they are intended to create improvements in Internal Process. These improvements are in turn supposed to positively affect customers’ behavior and thus lead to financial benefits (The diagram above illustrates this type of linkage). By creating cause and effect links an entire strategy can be clearly expressed in a measurable way that can be monitored and corrected as needed.

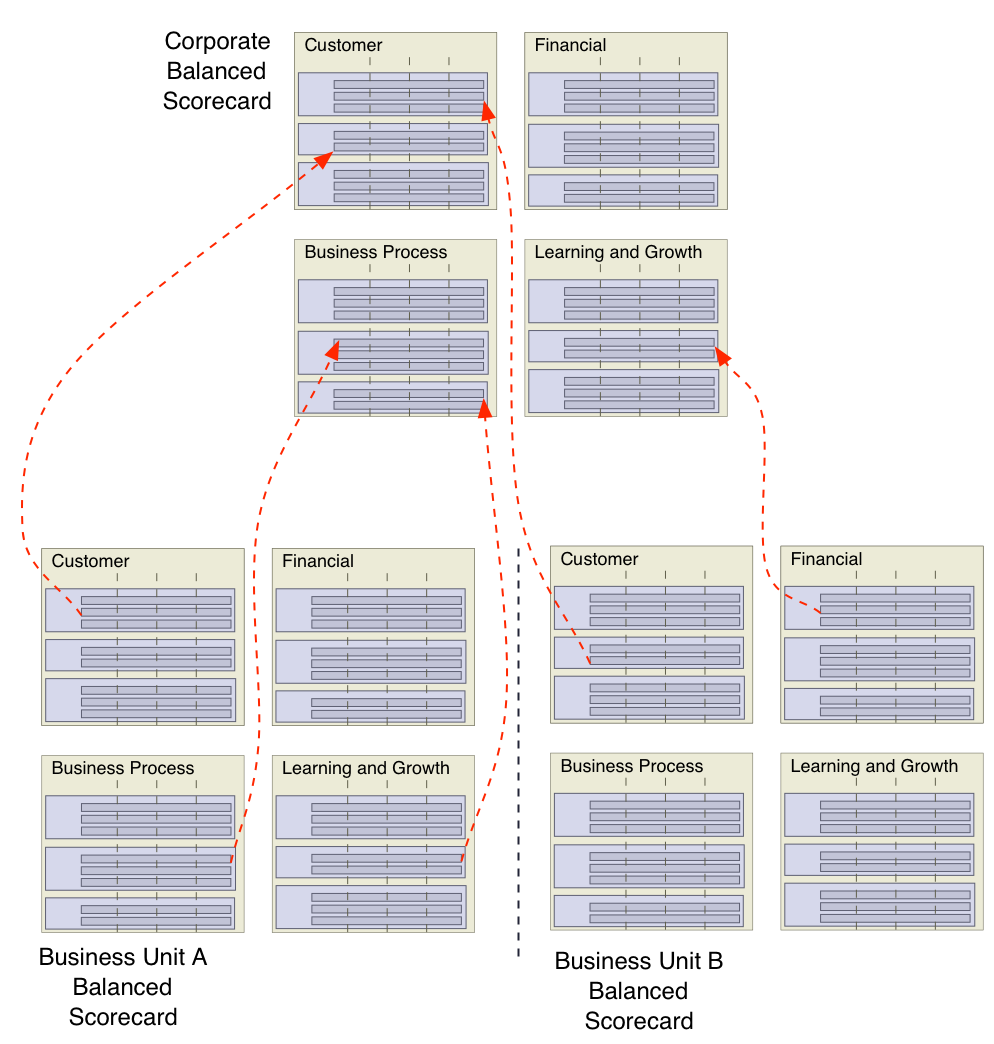

Cascading the Balanced Scorecard through an organization

After defining a corporate balanced scorecard an obvious next step is to cascade balanced scorecards down through the organization. Just as a balanced scorecard can be developed for an entire corporation, one can also be developed for a business unit within a corporation, or even a team within a business unit. Kaplan and Norton insist that the structure of balanced scorecards must reflect the organizational hierarchy. Presumably this ensures unambiguous ownership of goals and objectives although they offer no explanation. Ensuring that lower level balanced scorecards are aligned with higher levels is crucial. The goals and objectives at lower levels should be clearly linked of those at higher levels that they support. The process of cascading a balanced scorecard is not easy. It is often difficult to map the general measures defined at the corporate level to specific measures that the business unit can affect.

Kaplan and Norton take care to point out that the four perspectives they define are not the only ones that can be used. Unfortunately many practitioners of this approach have reduced these four perspectives to unchallenged dogma. Despite this, in many cases, they are perfectly adequate. However it is my belief that as balanced scorecards are cascaded down an organization the relative importance of the different perspectives changes. In extreme cases perspectives may become unnecessary and some new ones may need to be added. This is particularly true in the case of Enterprise and System Architecture.

In a pervious article I described the interaction of Business Policy, Strategy, and Architecture in system design and concluded by saying

Understanding how a System Architecture supports it’s Business Strategy within the framework of an Enterprise Architecture and how these in turn support Corporate Strategy and ultimately Corporate Policy is essential if systems are to deliver business value. This is not easy and is one reason why so many systems fail to deliver business value. The difficulty stems from the ever-changing business environment that forces continuous changes in goals and objectives. Making the goals and objectives explicit and then tracking them as they change is the only way to keep up with the game. But that is the topic for another time.

The Balanced Scorecard approach provides a way to handle these issues. The following sections describe an approach that handles the important distinction between corporate policy and strategy and introduces a new additional perspective to the four suggested by Kaplan and Norton that should be used when enterprise and systems architectures are involved.

Corporate Policy as a subset of Corporate Strategy

The goals and objectives of the corporate balanced scorecard should be labeled to indicate if they are corporate policy and therefore public knowledge or internal and therefore confidential. Corporate Policy is the subset of corporate goals and objectives that are discussed with investors and industry analysts in order to explain the corporate strategy. Some of the corporate strategy is kept internal to retain strategic advantage and strategic flexibility. These differences are important because it is easier to change internal strategy than it is to change corporate policy. Changes to corporate policy must be explained to investors and financial analysts. Changes to internal strategy need only to be communicated within the organization.

The Quality Attribute Perspective

When developing an enterprise architecture a new perspective should be added to the existing corporate balanced scorecard. This perspective should define the quality attributes of the enterprise architecture. Quality attribute definition has long been used to specify desirable capabilities of software systems (I will cover the definition of software quality attributes (capabilities) in another article). What this approach has lacked in the past is a way to link the goals and objectives for quality attributes into the overall corporate and business strategy. By adding a quality attribute perspective to an existing balanced scorecard this problem can be solved. The new quality attribute perspective should be subservient to all other perspectives. Every goal and objective on the new perspective must be linked to one or more other goals or objectives in the other perspectives. There is absolutely no point in defining goals and objectives for enterprise architecture quality attributes unless they support some other business objective. Enterprise architecture has no meaningful purpose independent of the enterprise! By making the relationship between the quality attribute perspective and the rest of the balanced scorecard explicit changes in corporate strategy can be assessed in terms of their impact on the enterprise architecture and vice versa.

After the corporate balanced scorecard has been cascaded down through the organization. A similar process can be performed for the quality attribute perspective. If a business unit is developing one or more software applications then a quality attribute perspective should be developed for each system. Each quality attribute perspective must be derived from the Corporate Enterprise Architecture Quality Attributes. And must be subservient to, and supportive of, all the other perspectives created for the business unit.

It could be argued that software quality attributes to do not warrant their own perspective as they are merely a specialized form of internal business process objective. For some organizations this may be the case. But given the cost of software systems, the increasing reliance placed on them by businesses, the risks associated with failure and the alarming frequency with which they do fail. I believe software quality attributes deserve special attention. In particular many problems caused by continuously changing business goals and objectives can be identified and managed with this approach. Identifying and traking the changing relationships between strategic objectives, of different perspectives, at various levels, within an organization is difficult. It requires the support and active participation of all parties, it is a political and organizational process as much as it is a technical one. Fortunately the process of consensus building within an organization is not the subject of this article.