Today Vannevar Bush (rhymes with achiever) is often remembered for his July 1945 Atlantic Monthly article As We May Think in which he describes a hypothetical machine called a Memex. This machine contained a large indexed store of information and allowed a user to navigate through the store using a system similar to hypertext links. At the time of writing his essay Bush knew more about the state of technology development in the US than almost any other person. During the war, he was Roosevelt’s chief adviser on military research. He was responsible for many war time research projects including Radar, the Atomic Bomb, and the development of early Computers. If anyone should ever have been capable of predicting the future it was Vannevar Bush in 1945. He is an almost unprecedented test case for the art of prediction. Unlike almost anyone else before or since Bush was actually in possession of ALL the facts – as only the head of technology research in a country at war could be.

The Editor of the Atlantic Monthly introduced the article as follows:

As Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, Dr. Vannevar Bush has coordinated the activities of some six thousand leading American scientists in the application of science to warfare. In this significant article he holds up an incentive for scientists when the fighting has ceased. He urges that men of science should then turn to the massive task of making more accessible our bewildering store of knowledge. For years inventions have extended man’s physical powers rather than the powers of his mind. Trip hammers that multiply the fists, microscopes that sharpen the eye, and engines of destruction and detection are new results, but not the end results, of modern science. Now, says Dr. Bush, instruments are at hand which, if properly developed, will give man access to and command over the inherited knowledge of the ages. The perfection of these pacific instruments should be the first objective of our scientists as they emerge from their war work. Like Emerson’s famous address of 1837 on “The American Scholar,” this paper by Dr. Bush calls for a new relationship between thinking man and the sum of our knowledge. -THE EDITOR

The essay was prescient in many respects. However, it failed to anticipate several innovations that are fundamental to modern information management and made many predictions that are only partially correct. It is easy to ignore Bush’s off-target predictions and focus solely on what he got right, but this would be a waste of an opportunity. By examining the innovations Bush failed to anticipate and the predictions he got half-right, and even wrong, we can develop a better understanding of prediction itself.

Background

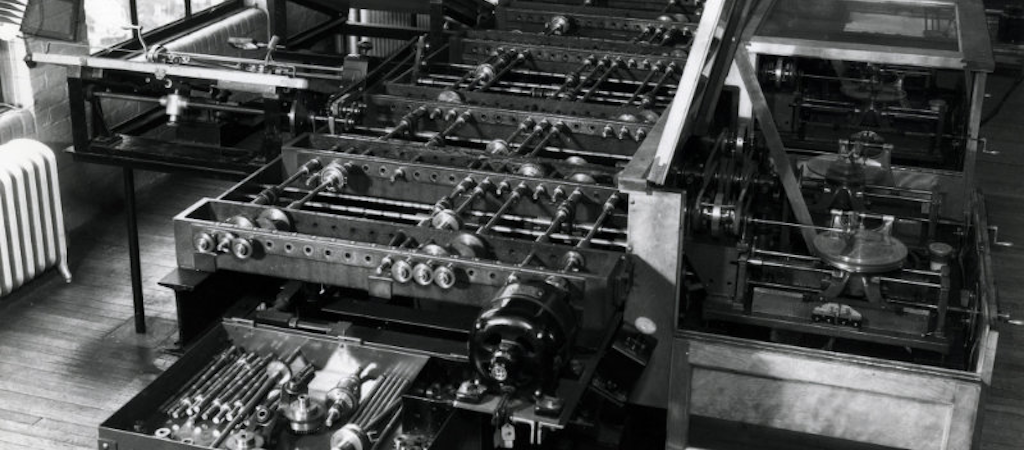

Before the War Bush had been involved in the design and construction of analog computers for many years. At MIT He led colleagues and students in the development a series of analog machines that could solve differential equations. In 1927 Bush and others started developing the Integraph – a machine capable of solving first order differential equations. This was followed by the Bush Hazen Differential Analyzer, a general purpose equation solver that could solve 6th order differential equations. The Bush Hazen machine was operational at MIT in 1932 and served as the prototype for many similar machines built elsewhere. Finally in December 1941 the Rockerfeller Differential Analyzer (RDA) became operational at MIT. Financed by the Rockefeller Foundation, this machine used vacuum tubes and relays. It weighed 100 tons and was immediately classified. It spent the war calculating artillery tables. By the Wars end the RDA was redundant having been superceded by totally electronic machines like the ENIAC.

As Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development Bush was Roosevelt’s chief adviser on military research. He was an engineer, an expert administrator, a capable politician, and was not afraid of fight. He allocated funds and managed priorities for many of the major US funded research projects of the Second World War. At the end of the war when he wrote the essay he knew many secrets.

Veiled Secrets not Predictions

Vannear Bush’s paper was published at the dawn of the digital age in July 1945. Many of the “predictions” it contained were merely veiled descriptions of secret wartime developments that had yet to be declassified. When Bush wrote his essay the great electronic computers that had been developed to aid the war effort were still secret. The ENIAC was the first of these machines to be publicly announced by the New York Times on February 16th, 1946. Bush undoubtedly knew of ENIAC and other machines under development. The following quote from the essay is stated as a prediction but is actually a fairly accurate description of the ENIAC.

Moreover, they [computers] will be far more versatile than present commercial machines [punch card tabulators and hand calculators], so that they may readily be adapted for a wide variety of operations. They will be controlled by a control card or film, they will select their own data and manipulate it in accordance with the instructions thus inserted, they will perform complex arithmetical computations at exceedingly high speeds, and they will record results in such form as to be readily available for distribution or for later further manipulation. Such machines will have enormous appetites. One of them will take instructions and data from a whole roomful of girls armed with simple key board punches, and will deliver sheets of computed results every few minutes. There will always be plenty of things to compute in the detailed affairs of millions of people doing complicated things.

The first atomic bomb was detonated at the Trinity site in New Mexico on July 16, 1945. a few weeks after the essay was published. Bush is said to have had a nervous collapse after witnessing the test detonation. It’s success must have been a tremendous relief for Bush who had persuaded the President to commit the $2 Billion necessary to build the bomb. The following paragraph describing the impact of the war on scientific research, especially physics, seems to refer to the massive Manhattan Project and all the physicists involved.

It is the physicists who have been thrown most violently off stride, who have left academic pursuits for the making of strange destructive gadgets, who have had to devise new methods for their unanticipated assignments. They have done their part on the devices that made it possible to turn back the enemy, have worked in combined effort with the physicists of our allies. They have felt within themselves the stir of achievement. They have been part of a great team. Now, as peace approaches, one asks where they will find objectives worthy of their best.

Predictions

Bush starts his visionary predictions by suggesting that computers could be made to manipulate premises in than same way they manipulate numbers.

It is readily possible to construct a machine which will manipulate premises in accordance with formal logic, simply by the clever use of relay circuits. Put a set of premises into such a device and turn the crank, and it will readily pass out conclusion after conclusion, all in accordance with logical law, and with no more slips than would be expected of a keyboard adding machine.

He then describes the Memex as a personal desktop interactive device. However it is here that his foresight breaks down because the Memex it described as analog not digital. While it contained some computing components information was stored photographically on microfilm and retrieved electro-mechanically. The Memex was nothing like the room sized computers of the late 1940′s. In the 1946 New York Times article announcing the ENIAC the new computer was described as “an amazing machine which applies electronic speeds for the first time to mathematical tasks hitherto too difficult and cumbersome for solution.” It took a long time before people began to implement Bush’s suggestion that computers could manipulate premises as well as numbers. Alan Turing had understood that computers were manipulators of symbols and that those symbols could represent any concept. But this knowledge was tightly bound to his work on code breaking and he in turn was bound by secrecy not to discuss it.

Ultimately Bush’s prescience was limited by two factors: Failure to anticipate the emergence of fundamentally new technologies, and failure to predict the exponential improvements in many areas that such inventions would support.

The Relay gave way to the Thermionic Value which in turn gave way to the Transistor which itself was replaced by the Silicon Chip. Each paradigm shift maintained the exponential rate of growth in computing power. Bush could not have predicted this chain of technological advances. But as Moore has shown the exponential growth it has produced is predictable.

In 1945 the ENIAC could not even store its own meager program in what little memory it had and all data was stored externally. The idea of storing vast quantities of data digitally was not considered realistic, it was accepted that there had to be some form of external physical storage. Bush merely replaced the punched card with a microfilm. But memory storage advanced in a similar way to computing power, from mercury delay lines, and magnetic drums to William’s tubes, magnetic core memory and tape, to modern chip based RAM, and high speed disc drives. Today a standard home computer is typically shipped with over a 100 Gigabytes of storage and several hundred Megabytes of memory.

Bush’s biggest failings were in predicting implementation details and his most accurate predictions concerned the interaction of people and technology. The Memex is eerily similar to a networked PC running a web browser. Even Bushes description of the wearable camera is remarkably close. We don’t wear our cameras because they double as portable phones but everything else about them from their size to the number of photos they can take is remarkably accurate.

Conclusions

Reading this essay with hind sight, and knowing that large amounts of information were still secret in July 1945, one is forced to wonder who was the intended audience of the essay. The essay seems to be an inverse call to arms, aimed at the scientists and researchers who would have recognized their own secret war time work between Bush’s lines. In effect Bush was suggesting a path for post war research and development based on his uniquely broad knowledge of the state of technology. The Memex was a technological phoenix to be built from the ashes of wartime science. It was an example of how various wartime advances could be combined to create something awesome but benign. A modern library of Alexandria on every desktop.

The ability to see even a decade into the future is impressive. That Vannevar Bush was able to see much further is remarkable and a testament to his brilliance. It would be a shame if he were only remembered as the inventor of hypertext. When in fact he foresaw the information revolution.