This is the first of an occasional series of reviews I intend to write to illustrate some important general traits of ontologies. In each review I will dissect an ontology and examine why it succeeded or failed. In this essay I mention concepts that are defined in my previous essay. Judging the likely success of an ontology. This first review covers an ontology called the Common Basic Specification (CBS) that was designed in the late 1980s to bring much needed standardization and rationalization to the fragmented information management processes of the British National Health Service (NHS). It persisted in various forms until the late 1990′s when it was finally abandoned. This is my explanation of why it failed.

I have been living in the US now for 6 years and have come to recognize a common reaction among Americans whenever the NHS is mentioned. They all try to hide it, but a patronizing look comes over them. It doesn’t matter how much you tell them that doctors in the NHS wash before they go into surgery, and even use anesthetics these days, Americans just can’t help feeling sorry for anyone who has to suffer under a 3 rd world healthcare system. So before I explain the CBS it is probably worth describing the NHS.

Background

The NHS is the largest employer in Europe it is the main provider of healthcare for the entire United Kingdom (pop 60 million). It’s annual budget is about 5 to 6 percent of the GDP of the United Kingdom. In 2002 that amounted to about 64 billion GBP which at current exchange rates is approximately 115 billion USD. By contrast the US spends about 15 percent of its GDP on healthcare and Americans live on average one year longer than the British. A more detailed breakdown of staffing and budget allocation for the NHS is available here. Primary healthcare in the UK is delivered through about 10,000 General Practices and about 2000 Hospitals, most with less than 100 beds. There are a few large Hospitals with up to 1000 beds, these larger hospitals are usually teaching Hospitals. All these numbers are approximate but they give a general idea of the scale of the NHS.

In the late 1980s it became apparent that the same information management problems were being encountered over and over again in hospital after hospital throughout the UK. Not only that, but they were being solved poorly time and time again. This was obviously wasteful. Hospitals had no reason to compete in the area of information management and every reason to cooperate. If these common problems could be solved correctly and then reused significant savings might be realized. At the same time the digital patient record became the holy grail of healthcare computing. In this vision of the future any patients complete medical history would be available anywhere it was needed and could be passed from GP practice to Hospital and back. It could even follow a patient as s/he moved around the country. The Common Basic Specification was suggested as the best way to ensure consistency across multiple solutions and thus enable standardization and portability of the digital patient record.

The Common Basic Specification

The Common Basic Specification ( CBS ) is a conceptual generic model of the activity of health care delivery.

[IT Standards Handbook - NHS Data Standards]

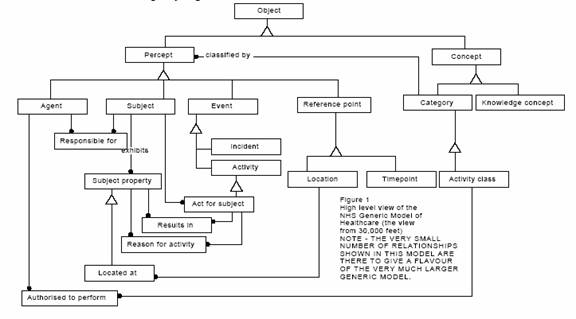

Definition of the NHS Data Model was started in 1986 and continued for several years. It was eventually renamed the Common Basic Specification (CBS). By 1992 a CBS Generic Model had been published. This was in effect a top level ontology (similar to the SUMO currently under development). It was developed for healthcare service delivery but it as can be seen from the diagram below it was universally applicable to any kind of service delivery.

Class descriptions for the figure

- Act for subject: An “Activity” that is directed towards a “Subject”.

- Activity: Purposeful and intentional “Event”

- Activity class: A kind of “Activity”.

- Agent: Role assumed by a “Subject” enabling it to act purposefully

- Authorised to perform: The recording of the fact that an “Agent” may perform certain classes of “Activity”.

- Category: Abstraction on the basis of common properties.

- Concept: “Object” which is a unit of thought.

- Event: Something which happens.

- Incident: “Event” occurring without known volition.

- Knowledge concept: A collection of “Concepts”, the relationships between them and the reasons for them.

- Located at: A “Location” for a “Subject”.

- Location: Point or piece of space.

- Object: Part of the conceivable or perceivable universe

- Percept: Perceived or inferred to exist

- Reason for activity: The identification of a “Subject property” as the reason for performing or planning an “Activity for > subject”.

- Reference point: Point or piece of time or space.

- Responsible for: The responsibility that an “Agent” has for a “Subject”.

- Results in: A means of establishing that an “Activity for subject” has resulted in a “Subject property”.

- Subject: “Percept” which is one or more physical objects.

- Subject property: Anything that describes a subject:** location, identity, characteristic etc..

- Timepoint: Point or span of time.

The initial publication of the CBS was found to be too high level. The model was hurriedly reworked and republished in 1993 as a series of CBS Application views one of which was later renamed the CBS Clinical View. This view was a slightly lower level ontology. After nearly 5 years and 5 million GBP had been invested in the model it was decided to use it as the foundation for a series of “demonstrator projects”. This work began in 1992/3. I was involved in the largest of these projects where the CBS was to be used as the foundation for an entire Hospital Information Support System. This system was to cover every aspect of hospital information management: patient master index, inpatient and outpatient management, orders and results reporting, , maternity, pharmacy, and many other ancillary activities including; clinical laboratories, laundry, and facilities management. By using the CBS as a conceptual model the final system was intended to be reusable across the NHS and be fully “future-proofed”. The system took almost 3 years to build and while it was successful in the first hospital it was only reused once.

In 1998, 3 years after the Hospital Information Support System was completed the model was redefined yet again and renamed the NHS Healthcare Model (HcM). But by this point it was too late. No one believed in the blue fairy of future proofing anymore and the model was abandoned. It is no longer even available online from any official NHS website. However, last year I downloaded a copy in anticipation of writing this article. So here is The Common Basic Specification (CBS) a.k.a. The NHS Healthcare Model (HcM). Take a look around and try drilling down on some of the diagrams to get a real flavor of the model. (If you want a complete copy just send me an email and I will send a zipped file. Please don’t over stress my poor machine by downloading the whole thing.)

As ontologies go the Common Basic Specification is large and complex, which is not surprising given its scope and the length of time it took to develop. The CBS was reworked and refined until it became a clean conceptual model for generic service delivery. It is; coherent – logical in the relationship of its parts, generic enough to handle any healthcare delivery use case, and it is mature – the corners have been knocked off. So why did it fail?

Reasons for Failure of the Common Basic Specification

Of the Millions of pounds spent on developing the CBS very little was spent on articulating the benefits of implementing a common standard or training people to use the model. Many potential beneficiaries of the model did not see the value of training staff to understand it. Implementing an ontology is a political activity. It requires persuasion, coercion and sometimes direct threats. Small specialized groups can be persuaded to agree on large complex ontologies but large groups find such agreement difficult and often impossible. It is almost as if there was a law governing the adoption of ontologies.

The size and complexity of an ontology is inversely proportional to the size and complexity of the community of agents that can be persuaded to adopt it.

But there is a more fundamental problem with top level ontologies that is not political. At higher levels of abstraction every conceptual model is subjective; there is always another way to model reality. It can be advantageous to deliberately take a contrary view precisely because it will lead to different conclusions that may offer competitive advantage over others. The field of Healthcare delivery is large enough to accommodate many different world views. The CBS failed because it was the fossilization of a single world view.

Finally the Common Basic Specification took a top down reductionist approach to a fundamentally bottom up emergent problem. This same fundamental error is made by all top level ontologies. It is being made today by the developers of SUMO, an ontology doomed to the same fate as the CBS. As a professional body the IEEE ought to know better. A top down reductionist approach is useful for constrained problem domains but it is the wrong strategy for broad areas of knowledge. Robert Graves understood the tradeoff between a top down and a bottom up and explained it better than I ever could in his poem In Broken Images.

In Broken Images

He is quick, thinking in clear images; I am slow, thinking in broken images.

He becomes dull, trusting to his clear images; I become sharp, mistrusting my broken images,

Trusting his images, he assumes their relevance; Mistrusting my images, I question their relevance.

Assuming their relevance, he assumes the fact, Questioning their relevance, I question the fact.

When the fact fails him, he questions his senses; When the fact fails me, I approve my senses.

He continues quick and dull in his clear images; I continue slow and sharp in my broken images.

He in a new confusion of his understanding; I in a new understanding of my confusion.

Robert Graves