The Evolution of Cooperation by Robert Axelrod is an outstanding book. First published in 1984 it has increased in significance with the evolution of the Internet. In the book Axelrod examines how cooperation can emerge and stabilize in multi-participant environments. The book is fascinating as an analysis of the evolution of cooperation, but is of particular interest to anyone seeking to establish effective; social software systems, peer-to-peer networks, or multi-player gaming environments. Axelrod builds his thesis on the analysis of a gaming tournament he organized. He invited multiple people from many different fields; economics, computer science, evolutionary biology, etc, to submit computer programs employing well defined strategies to play a series of games of Prisoner’s Dilemma. Each program played several hundred games against every other program. The results were surprising and enlightening.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma

In the game of Prisoner’s Dilemma there are two players, who each have two choices. Each player chooses simultaneously, to cooperate or to defect. If they both choose to cooperate they both get R – the reward for mutual cooperation. If they both choose to defect they both get P – the punishment for mutual defection. If one cooperates and the other defects then the defector gets T – the temptation, and the cooperative player gets S – the suckers payoff. The dilemma comes from the fact that the best strategy depends on the opponent’s strategy and a smart player knows this, so players must both second guess each other.

The following table shows the scoring system used by Axelrod for the Prisoner’s Dilemma tournament.

| Cooperate | Defect | |

|---|---|---|

| Cooperate | R=3, R=3 Reward for mutual cooperation | S=0, T=5 Sucker’s payoff, and temptation to defect |

| Defect | T=5, S=0 Temptation to defect and sucker’s payoff | P=1, P=1 Punishment for mutual defection |

The results above are one specific case. Any game is a Prisoner’s Dilemma if it satisfies the following inequalities:

T > R > P > S

And

R > (T+S)/2

(This second inequality means it is better to cooperate than alternately defect and cooperate)

In the Axelrod’s tournament one of the simplest strategies was the clear winner. Axelrod calls this strategy Tit-for-Tat – Cooperate on the first move and thereafter do whatever the opponent did on the previous move. Why this strategy is so successful and what it means is the subject of the rest of the book.

The Shadow of the Future

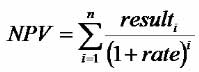

Axelrod defines a term “w” for weight (or importance) of a future result. He assumes that w always takes a value between zero and one (0 < w < 1). If w is 1 then future results are as important as current results, but if w is 0.5, for example, then future results are half as important as current results. The current value of the next result is calculated by multiplying the payoff by w. High values of w mean the future is more important and low values mean it is less important. The net present value of a series of future results can be calculated according to this formula.

where w is equivalent to 1 / (1+rate)

Axelrod poetically calls the concept of a net present value “The Shadow of the Future”. Increasing w increases the size of the shadow whereas decreasing w decreases the size of the shadow.

The concept of the net present value of future earnings is a common one in economics and is fundamental in many investment decisions. Future earnings are less valuable than current earnings because of risk and opportunity costs. It is not certain that two players will actually meet again or that they will behave in a predictable manner. External influences could change the expected outcome. And there are usually alternative strategies that could be just as rewarding for the same risk.

Collective and Territorial Stability

If the game is played in rounds (where each round consists of many hundreds of turns) and the population of players using a given strategy in the next round is determined by the success of that strategy in the previous round. Then the concept of invasion and collective stability can be examined. A collectively stable strategy is one where a large number of agents using the same strategy cannot be “invaded” by a single agent playing a different strategy. Axelrod shows that some strategies can invade a larger group if there is more than one agent playing the invading strategy. He goes on to prove that Collectively stable strategies are also territorially stable. That is if agents can play only with adjacent agents the same rules apply.

Axelrod’s Propositions

Axelrod defines 8 propositions based on his analysis of the tournament. About half of the book is spent explaining these propositions.

- If the Discount parameter, w, is sufficiently high, there is no best strategy independent of the strategy used by the other player

- The Tit-for-Tat strategy is collectively stable if and only if, w is large enough. This critical value of w is a function of the four payoff parameters, T, R, P, and S

- Any strategy which may be the first to cooperate can vbe collectively stable only when w is sufficiently large

- For a nice strategy to be collectively stable, it must be provoked by the very first defection of the other player

- The strategy Always-Defect is always collectively stable

- The strategies which can invade Always-Defect in a cluster with the smallest value of p (the weighted average score an invader gets from games with other invaders and incumbents) are those which are maximally discriminating, such as Tit-for-Tat

- If a nice strategy cannot be invaded by a single individual, it cannot be invaded by a cluster of individuals either

- If a rule is collectively stable, it is territorially stable

How to do well

Axelrod provides four maxims for how to do well as a participant in situations similar to iterated games of Prison Dilemma.

- Don’t be envious – The Prisoner’s Dilemma is not a zero sum game. It is ok if your “opponent” does better than you. In fact if they don’t do at least as well as you then you are not cooperating enough.

- Don’t be the first to defect – Defection is an effective form of punishment but it is costly for both parties, it can lead to long periods of alternating defection. Stay away from defection until forced to act.

- Reciprocate both cooperation and defection – Reciprocity is a double edged sword. You must be prepared to consistently punish defectors as quickly as you reward cooperators.

- Don’t be too clever – Consistency is important, reciprocity works as a strategy if your opponent can predict your next move. Tit-for-Tat is successful partly because it is a transparent strategy.

How to encourage cooperation

Axelrod provides another set of maxims for those trying to encourage cooperation among players.

- Enlarge the shadow of the future – The net present value of future earnings can be increased in several ways. Increase the frequency of interactions between players, and increase the importance of the current game of future games. The importance can be increased by making a players actions a matter of public knowledge. This is the beginnings of reputation.

- Change the payoffs – Changing the payoffs so much that the inequalities defined above no longer hold true will destroy the game, but within the inequalities there is still room for optimization. Increasing R or decreasing T and P can all have encouraging effects

- Teach people to care about each other – Ethics and ritual often evolve in environments of iterative Prisoner’s Dilemma. These emergent features serve to enforce socially acceptable rules of conduct and can change players perception of the game to the point where cooperation is more “desirable” than the temptation to defect.

- Teach Reciprocity – Tit-for-Tat is fair but it has additional advantages. Tit-for-Tat encourages other players to use similar strategies. Players using Tit-for-Tat police their opponents and therefore provide a secondary benefit to other players using Tit-for-Tat

- Improve recognition abilities – Cooperation works effectively where players can recognize each other and remember how a given player behaved last time they met. Recognition and memory can be improved in several ways. Labels stereotypes, status and reputation can all play a part. Labeling players and categorizing them into stereotypes can help make large numbers of players manageable and make it easier to make fast decisions. Reputation is an emergent property of social groups. Players are generally recognized by the group as being reliable or unreliable. This is both a form of labeling and of collective memory.

Shirky’s Restatement

In his recent essay A Group is its own Worst Enemy Clay Shirky simplifies and restates similar findings by suggesting “four things to design for” when designing a social software system:

- If you were going to build a piece of social software to support large and long-lived groups, what would you design for? The first thing you would design for is handles the user can invest in.

- You have to design a way for there to be members in good standing. Have to design some way in which good works get recognized. The minimal way is, posts appear with identity. You can do more sophisticated things like having formal karma or “member since.”

- You need barriers to participation. This is one of the things that killed Usenet. You have to have some cost to either join or participate, if not at the lowest level, then at higher levels. There needs to be some kind of segmentation of capabilities.

- You have to find a way to spare the group from scale. Scale alone kills conversations, because conversations require dense two-way conversations. In conversational contexts, Metcalfe’s law is a drag. The fact that the amount of two-way connections you have to support goes up with the square of the users means that the density of conversation falls off very fast as the system scales even a little bit. You have to have some way to let users hang onto the less is more pattern, in order to keep associated with one another.

Emergence of Social Structures at the boundary of Cooperation and Defection

These lessons can be usefully applied to a variety of networked communities such as; peer-to-peer networks, multi-player gaming environments, and other social software systems if the community in question is playing a close analogue of the Prisoners Dilemma. This is true when the payoff scheme has equivalents to the payoffs R,P,T,S, and these equivalents satisfy, or can be made to satisfy, the inequalities T > R > P > S and R > (T+S)/2.

In his fine book Complexity: The Emerging Science at the Edge of Order and Chaos. , Mitchell M. Waldrop states that systems evolve most rapidly when they are pushed to the edge of chaos and order because this is the region where complexity emerges spontaneously. The inequalities that define the Prisoner’s Dilemma describe a similar boundary, between cooperation and defection, where complex social structures like ethics, ritual, and reputation emerge. I believe the most interesting social environments are the most adaptive environments, that support the emergence of complex social structures, that are only possible because both cooperation and defection are permitted. I believe it is therefore worth pushing networked environments towards this edge by making cooperation only slightly more attractive than defection. In other words R > (T+S)/2, but only just!

In many cases existing environments could be greatly improved if the payoff scheme were brought more into balance. It is common for the payoff scheme of these environments to be out of balance, either defectors go unpunished or there is no opportunity to defect and everyone becomes a sucker ripe for exploitation. By applying some of the maxims defined by Axelrod the payoff schemes of these environments can be moved towards a more balanced state typical of the Prisoner’s Dilemma. The important point to realize is that the option to defect is necessary because it is this option that drives the emergence of many social structures whose purpose is to encourage cooperation. These emergent features are only found where they are necessary to tip the balance between cooperation and defection in favor of cooperation.