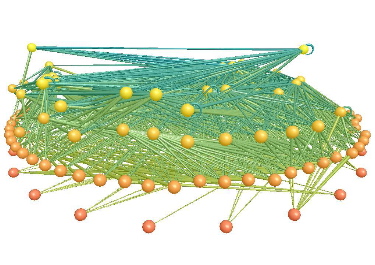

This diagram shows a food web, The nodes are species and the lines show predator-prey relationships between the species. Species at higher trophic levels eat those lower down in the web. This particular food web is for Little Rock Lake in Wisconsin and was produced by Neo D. Martinez of San Francisco State University, Romberg Tiburon Center for Environmental Studies.

Enough food webs have now been cataloged and described in detail for them to be studied as a general class of system using the techniques applied to the study of other networks. There are only a few descriptions of these studies outside the scientific literature. The California Academy of Sciences quarterly magazine – California Wild had this article called Untangled Food Webs and the BBC ran this story Life’s not so complicated Web but beyond that there does not appear to be much out there.

Searching the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) for papers published since January 2000 with the search string “food web” in the title or abstract yields 104 results (2003-04-28) and after a visual examination of these papers only 5 seem to deal with the study of food webs as a distinct phenomenon.

Below I have attempted to summarize these articles and papers. All the errors and omissions are my doing. Please check the sources I have linked to above before you draw any conclusion based on my summary, I am not an expert.

All food webs seem to share similar properties

Food webs with more than around 12 species appear to have common properties that seem largely independent of the particular ecosystem they describe. These properties allow interesting predictions to be made about food webs and the species they contain. For example; the number of cannibalistic species, the ratio of species with specialized diets to species with broad non-specialized diets, and the maximum length of possible food chains can all be predicted.

Big fish tend to be less common than the little fish they eat

There appears to be a roughly inverse relationship between body mass and abundance for individual species within food webs. In one study body mass and abundance were each found to vary by at least 10 orders of magnitude but biomass abundance (average body mass times numerical abundance) varied by only 5 orders of magnitude. In addition species with small body mass tend to appear low in the food web and are numerically abundant.

Food webs are highly connected and easily disrupted

In one study of 16 food webs with 25-172 nodes from variety of aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems food webs were found to have higher connectance (the fraction of all possible links between nodes that actually exist in the network) and smaller size than other types of networks that were studied. The complex feeding relationships between species typical of high connectance food webs can mean population fluctuations of one species dramatically affect another. There is evidence to suggest this ripple effect rarely travels more than 3 links away from the source. However the high connectance of food webs (on average species in a food web are just two links apart and >95% of all species are within 3 links of each other) means that biodiversity loss and species invasion may have a greater effect on ecosystems than previously thought. The introduction of wild pigs to the California Channel Islands is thought to be an example of this knock on effect. Piglets provided a bountiful food source for golden eagles, that turned to the native island fox as a food source when the piglets were out of season, thus allowing the population of island skunks to soar. An attempt is being made to put the Channel Islands ecosystem back to what it was. A mass cull of pigs likely to take 6 years and a captive breading program for the few remaining foxes is now underway.

Food Webs interact with each other

In a study of contiguous food webs, a stream and the deciduous forest it ran through, the two food webs were shown to exchange insect prey during different seasons. During spring adult insects emerged from the stream and where eaten by birds and during summer insects fell into the river and were eaten by the fish. This exchange represented a reciprocal alternating subsidy.