The measurement and management of time is something most people give little thought to. But when designing Internet based systems time presentation, manipulation and management can rapidly become a major headache. Just when you think youve got it nailed some other unanticipated problem arises. The regular failure of systems designers to get this right is a classic example of the principle of inappropriate parsimony.

The world is a sphere that rotates on its axis once every 24 hours and takes 365 days to rotate around the sun, more or less. Its very simple. But, the more or less part is vitally important. The world is not actually a sphere it is an oblate spheroid. It does not rotate every 24 hours it takes a ever-so-slightly longer than that and its getting slower, it wobbles on its axis which by the way is inclined to the plane of its rotation around the Sun. And as we all know it takes about a 1/4 of a day longer than a year to rotate around the Sun, more or less, and this time period is also increasing. Add to this the vagaries of international politics, national pride and public safety and you have a pretty complex system. All these factors affect the measurement and management of time. Given this complexity its not difficult to see why system designers try to simplify the conceptual model of the real world on which they base their solutions. However, this is the wrong thing to simplify. The solution can and should be simplified but the conceptual model on which it is based must be high fidelity not an approximation.

Time measurement in the real world

International Time Zones

Imagine the earth as a giant orange with 24 equally sized segments. Each segment takes up 1/24th of the earths circumference at any latitude. If two observers are standing on the same line of latitude, for example the equator, and they are exactly one segment (15 degrees) apart then there will be one hour difference between each observers local time. One of the observers will experience midday exactly 1 hour before the other. If the observers are exactly 2 segments apart then there will be 2 hours difference and so on.

By international treaty these segments are called international time zones. The first segment is called UTC-0 and is centered in the Greenwich Meridian that passes through both poles and Greenwich in London, England. This is the 0 degree line of longitude. International Time Zones are numbered, east of London they are positive and west of London they are negative as follows.

(…. UTC-3, UTC-2, UTC-1, UTC0, UTC+1, UTC+2, UTC+3…..)

In case you were wondering UTC-12 does not exist it is called UTC+12. The numbers refer to the offset in hours from the Greenwich Meridian. So UTC-8 is 8 hours behind UTC0. The time in the UTC0 time zone is considered to be the “base” time. All other times are relative to UTC. UTC stands for Coordinated Universal Time or just Universal Time. (Yes! the Acronym has the letters the wrong way round. The French insisted on having it that way!). “Greenwich Mean Time” is no longer the international base time it has been replaced by UTC.

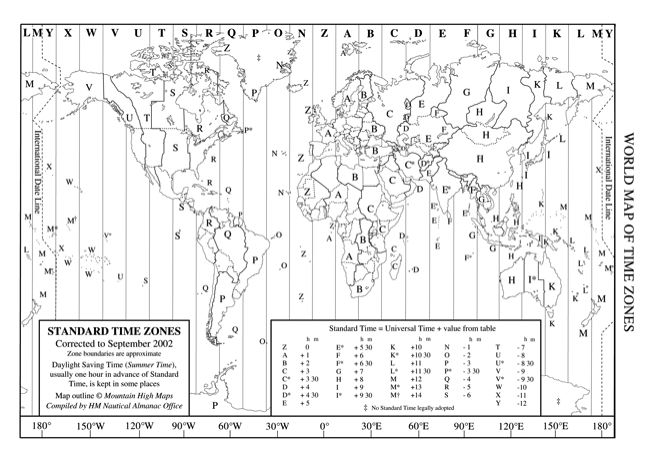

The main point to understand is that each International Time Zone defines a precise geographical area of the earth’s surface and an offset in hours from Universal Time. Each area is exactly 15 degrees wide, they cut across countries without regard to national borders or the decisions of local governments. But we all know that time often changes as we cross state borders not as we cross some arbitrary line defined by geometry. So what is going on? Thinking of International Time Zones as geometrically rigid is not a common practice as this map shows. Most people and even organizations confuse International Time Zones with Local Civil Time Zones. Even the name of this map is oxymoronic. There is nothing “standard” about the areas it defines, they change regularly forcing the map to be redrawn on a yearly basis.

Local Civil Time

Each country in the world, and sometimes each administrative subdivision within a country, aligns itself with an International Time Zone and bases it’s own definition of Civil Time on this alignment. Choosing which International Time Zone to align with involves the evaluation of several factors; Maximizing useful daylight hours, the Time Zones chosen by trading partners, national pride etc.

For Example the west coast of North America including administrative sub-divisions in Mexico, the USA (but not Alaska) and Canada have all aligned themselves with the UTC-8 International Time Zone even though the west coast of Canada lies mostly in the UTC-9 International Time Zone. The result is a region with the same offset in hours from UTC running from the Yukon Territory of northern Canada to half way down Baja California, Mexico. Each country and subdivision has named its Local Civil Time; in Canada it is called Pacific Time as it is in the USA but in Mexico it is called America/Tijuana Time.

Countries cannot arbitrarily redefine or rename International Time Zones all they can change is their own definition of Local Civil Time. So Local Civil Time in India is defined as being 5 ½ hours ahead of Universal Time. This is convenient for India because of it’s geographical location (straddling the boundary between UTC+5 and UTC+6) but there is no International Time Zone called UTC+5.5.

Much confusion results from the naming of International Time Zones UTC+3 is the name of a geographical area that is 3 hours ahead of Universal Time. However the name is also convenient shorthand for the offset from Universal Time. This leads many people to concluded that UTC+5.5 is the name of an International Time Zone. While it is plausible it is not accurate. There are only 24 International Time Zones.

Daylight Saving

Daylight Saving is the process of changing Local Civil Time, by adding or subtracting a fixed time period, usually and hour. This adjustment is carried out seasonally and has the effect of extending the amount of daylight available during the standard 9-5 working day. It has been shown that this simple adjustment can save lives by allowing people to travel to and from work during daylight hours. Continuing the example above there are two versions of US Pacific Time, Pacific Standard Time and Pacific Daylight Time. Pacific Standard Time is UTC -8 hours. But Pacific Daylight time is UTC -8 hours, + 1 hour, (effectively UTC -7 hours).

In the Northern Hemisphere the switch to daylight savings usually happens on the first Sunday of April at 2 am by adding one hour. The switch back usually occurs the on last Sunday of October again at 2 am by subtracting one hour. In the southern hemisphere everything is reversed. Daylight saving starts in September or October and ends in March or April.

From a systems design view point handling International Time Zones and Daylight saving is tricky. The end of daylight saving is the most disruptive time. Since the same hour is repeated. This can lead to severe problems if datestamps are recorded using Local Civil Time. Many designers do not realize that the system works differently in the northern and southern hemispheres, and Designers often assume that International Time Zones are the same thing as Local Civil Time.

Leap Years and Leap Seconds

Everyone knows that there are 365 days in a year, but every 4 years the Gregorian calendar makes a correction by adding an extra day because there are actually 365.25 days in a year. But this itself is merely an approximation. The rule for leap years is if it is divisible by 4 unless it is also divisible by 100 unless it is also divisible by 400 in which case it is a leap year again (So the year 2000 was a leap year!)

Every now and then leap seconds are added or taken away from UTC. This is achieved by adding, or subtracting, a second from the last minute, of the last day, of June or December. The last minute of 1996 was 61 seconds long. The reason for this adjustment is complex. If you want to understand then you need to look up the difference between International Atomic Time and Coordinated Universal Time. So far all leap seconds have been positive additions.

Recording Dates and Times for Internet Systems

One clean solution to the above problems is as follows

- All Times must include the date as well since, as you will see, the date can change depending on where we choose to display the time.

- All Times are recorded in UTC.

- All Times are recorded with the Name of the local Civil time used to record them and a few denormailzed attributes (Offset and Daylight Savings) for efficiency.

In this example dates are formatted as follows YYYY-MM-DD and all times are 24HR:MM:SS. This is how you would record 10 pm on May 18th 2002 in San Francisco

| UTC | Civil Time | Offset from UTC | Daylight Saving |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002-05-19 5:00:00 | Pacific Daylight Time | -8 | +1 |

Notice that the days are different. In San Francisco it is still the 18th but at Greenwich it is the 19th. The benefit of this way of recording dates is that all dates recorded anywhere in the world can be compared. Since they are all recorded in UTC we can order by the UTC value and get everything in chronological order. Furthermore we can recreate the format of the original entered date and time easily and any other Time Zone without too much trouble.

2002-05-19 5:00:00 Subtract 8 hours and then add 1 hour = 2002-05-18 22:00:00 (Pacific Daylight Time)

This even gives us a way to untangle switches from daylight saving back to normal time. Consider the following. (Remember the switch from Daylight Saving back to Pacific Standard Time happened at 2 am on October 27th).

| UTC | Civil Time | Offset from UTC | Daylight Saving | Time in San Francisco |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2002-10-27 09:30:00 | Pacific Daylight Time | -8 | +1 | 2002-10-27 02:30:00 (Pacific Daylight Time) |

| 2002-10-27 10:30:00 | Pacific Standard Time | -8 | +0 | 2002-10-27 02:30:00 (Pacific Standard Time) |

This demonstrates why recording UTC is essential to avoid repeating the same timestamps when switching from daylight savings back to normal time.

What this model lacks is a way to lookup when daylight saving comes into effect. For this a lookup table is required as follows

Civil Time Lookup Table

| Column Name | Example Value |

|---|---|

| Year | 2002 |

| Local Civil Time Name | Pacific Time |

| Country | USA |

| Administrative Subdivisions | Oregon, Washington, California |

| Daylight Saving Time Name | Pacific Daylight Time |

| Daylight Saving Time Offset | +1 |

| Daylight Saving Time Start | 2002-04-07 10:00:00 UTC-0 |

| Daylight Saving Time Stop | 2002-10-27 09:00:00 UTC-0 |

| Standard Time Name | Pacific Standard Time |

| Standard Time Offset | 0 |

| International Time Zone Name | UTC-8 |

| Offset from UTC | -8 |

When recording a time with this model you need to know the date and time and the civil time that is being used. Then a check on the lookup table can be used to set the required parameters such as offset and the daylight savings value. This is not particularly efficient since it requires a lookup every time a date-time is recorded.

Finally if you are going to all this trouble you really need access to a reliable system clock for accurate timestamps. This can be done by configuring Network Time Protocol.

There is one thing this model does not handle. In the event that a negative leap second is ever required this model will not work. The second in question will be repeated. This seems unlikely. Since the earth is slowing down in its rotation around the sun not speeding up.